February 23, 2017 / by / In deeplearning

Deep Learning 101 - Part 1: History and Background

tl;dr: The first in a multipart series on getting started with deep learning. In this part we will cover the history of deep learning to figure out how we got here, plus some tips and tricks to stay current.

The Deep Learning 101 series is a companion piece to a talk given as part of the Department of Biomedical Informatics @ Harvard Medical School ‘Open Insights’ series. Slides for the talk are available here and a recording is also available on youtube

Other Posts in this Series

Each post in this series is a collection of explanations, references and pointers meant to help someone new to the field quickly bootstrap their knowledge of key events, people, and terms in deep learning. In the same way that neural nets use a distributed representation to process data, reference materials for deep learning are scattered across the far flung corners of the internet and embedded in the dark ether of social media. The hope is that coalescing at least some of these materials into a central location will make it easier for new comers to start their own walk over this knowledge graph. This collection is intentionally peppered with trivia and articles from the popular press that are relevant to deep learning to keep things interesting and to provide context.

These posts are also inspired by the Matt Might Mantra of blogging:

The secret to low-cost academic blogging is to make blogging a natural byproduct of all the things that academics already do.

If Matt Might gives a suggestion, it’s probably a good idea to follow it.

I hope to keep this updated and fresh as new research is produced. Hopefully this can remain a point of reference in the future. So like Kanye’s Life of Pablo, the posts in this series will continue to change and evolve as new stuff happens. If you see something missing that you think should be added, leave a comment below or shoot me a message on twitter.

Introduction

Deep learning, over the past 5 years or so, has gone from a somewhat niche field comprised of a cloistered group of researchers to being so mainstream that even that girl from Twilight has published a deep learning paper. The swift rise and apparent dominance of deep learning over traditional machine learning methods on a variety of tasks has been astonishing to witness, and at times difficult to explain. There is a fascinating history that goes back to the 1940s full of ups and downs, twists and turns, friends and rivals, and successes and failures. In a story arc worthy of a 90s movie, an idea that was once sort of an ugly duckling has blossomed to become the belle of the ball.

Consequently, interest in deep learning has sky-rocketed, with constant coverage in the popular media. Deep learning research now routinely appears in top journals like Science, Nature, Nature Methods and JAMA just to name a few. Deep learning has conquered Go, learned to drive a car, diagnosed skin cancer and autism, became a master art forger, and can even hallucinate photorealistic pictures.

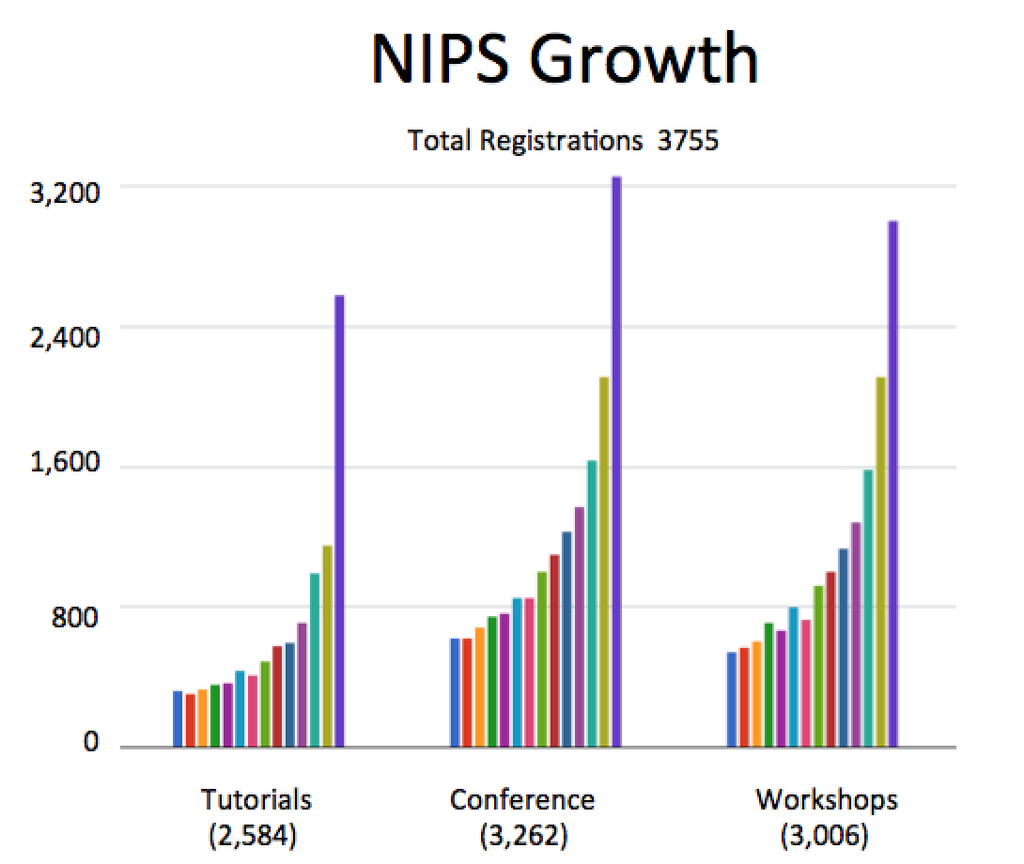

A good surrogate for interest in deep learning is attendance at the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS). NIPS is the main conference for deep learning research and has historically been where a lot of the new methodological research get published. Interest in the conference has surged in the last 5 years:

The chart only goes to 2015 and this year’s NIPS had over 6,000 attendees, so it doesn’t look like interest is close to leveling off anytime soon. Confirmation that we were entering a period of serious hype occurred during NIPS 2013 when Mark Zuckerberg made a surprise visit to recruit deep learning talent, and ended up convincing Yann Lecun to be the director of the Facbook AI lab.

What does all this hype mean? Why is this happening now? At a high-level, what we’ve witnessed is the synergistic combination of insights from optimization, traditional machine learning, software engineering, integrated circuit design, and serious sweat equity from a dedicated group of researchers, postdocs, and grad students. Though the main ideas behind deep learning have been in place for decades, it wasn’t until data sets became large enough and computers got fast enough that their true power could be revealed. With that said, it’s worth walking through the history of neural nets and deep learning to see how we got here.

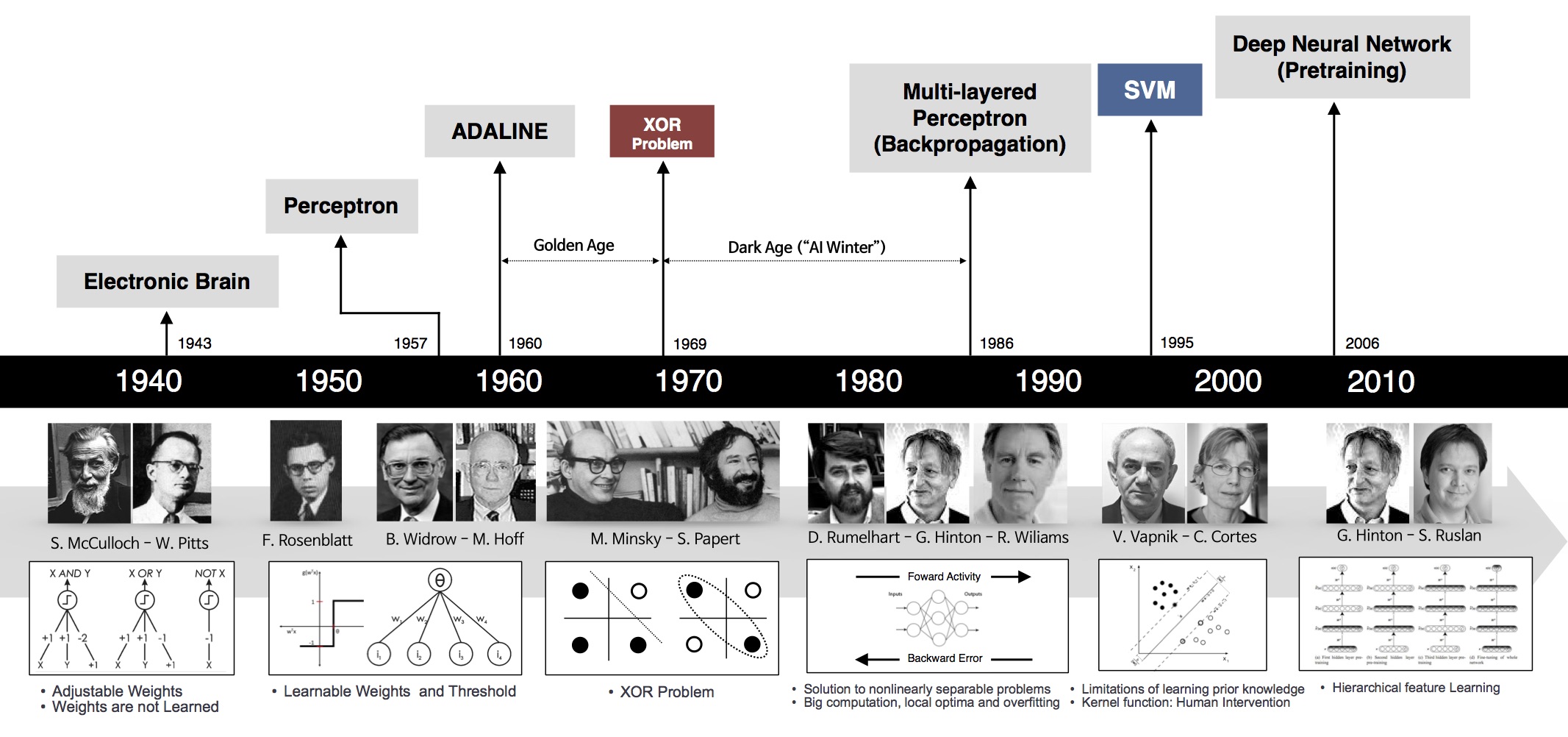

Milestones in the Development of Neural Networks

Note: I am not the creator of the above image. I have been unable to locate the original source. If this is your image please let me know so I can give you proper attribution.

Note: I am not the creator of the above image. I have been unable to locate the original source. If this is your image please let me know so I can give you proper attribution.

In The Beginning (1940s)…

The idea of creating a ‘thinking’ machine is at least as old as modern computing, if not even older. Alan Turing in his seminal paper ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ laid out several criteria to asses whether a machine could be said be intelligent, which has since become known as the ‘Turing test’. For some great explorations on variants of the Turing test, check-out Brain Christian’s book detailing his adventures with the Loebner Prize entitled The Most Human Human or check the amazing, dramatized version in Ex-machina.

Early work in machine learning was largely informed by the current working theories of the brain. The first guys on the scene were Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch. They had developed a technique known as “thresholded logic unit” and was designed to mimic the way a neuron was thought to work (which will be a recurring theme). There is a truly great story on the partnership of McCulloch and Pitts, available here that I highly recommend. Here’s a quote to get you started.

McCulloch was a confident, gray-eyed, wild-bearded, chain-smoking philosopher-poet who lived on whiskey and ice cream and never went to bed before 4 a.m.

Sounds like my kind of person. Picking the thread back up again, it isn’t until Frank Rosenblatt’s “perceptron” that we see the first real precursor to modern neural networks. For its day, this thing was pretty impressive. It came with a learning procedure that would provably converge to the correct solution and could recognize letters and numbers. Rosenblatt was so confident that the perceptron would lead to true AI, that in 1959 he remarked:

[The perceptron is] the embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence.

Queue the ominous music.

The First AI Winter (1969)

Rosenblatt’s perceptron began to garner quite a bit of attention, and one person in particular began to take notice. Marvin Minsky, who is often thought of as one of the father’s of AI, began to sense that something was off with Rosenblatt’s perceptron. Minsky is quoted here saying:

Rosenblatt’s perceptron began to garner quite a bit of attention, and one person in particular began to take notice. Marvin Minsky, who is often thought of as one of the father’s of AI, began to sense that something was off with Rosenblatt’s perceptron. Minsky is quoted here saying:

However, I started to worry about what such a machine could not do. For example, it could tell ‘E’s from ‘F’s, and ‘5’s from ‘6’s—things like that. But when there were disturbing stimuli near these figures that weren’t correlated with them the recognition was destroyed.

Along with the double-PhD wielding Seymor Papert, Minksy wrote a book entitled Perceptrons that effectively killed the perceptron, ending embryonic idea of a neural net. They showed that the perceptron was incapable of learning the simple exclusive-or (XOR) function. Worse, they proved that it was theoretically impossible for it to learn such a function, no matter how long you let it train. Now this isn’t surprising to us, as the model implied by the perceptron is a linear one and the XOR function is nonlinear, but at the time this was enough to kill all research on neural nets and usher in the first AI winter.

It’s hard to be mad at Minsky though, and after reading this New Yorker piece, he sounds like someone who is as close to the platonic ideal of a scientist and academic as a human can be. Here is a quote from the article the entice you to go read it:

When he was a student, he has said, there appeared to him to be only three interesting problems in the world—or in the world of science, at least. “Genetics seemed to be pretty interesting, because nobody knew yet how it worked,” he said. “But I wasn’t sure that it was profound. The problems of physics seemed profound and solvable. It might have been nice to do physics. But the problem of intelligence seemed hopelessly profound. I can’t remember considering anything else worth doing.”

The Backpropagandists Emerge (1986)

As the Minksy-induced snowpack began to melt, signs of life began to return to the neural net community. George Bool’s great-great-grandson, a man by the name of Geoff Hinton, finished his PhD studying neural networks in 1978 and by 1986 had moved to the institute for cognitive science at UC San Diego. Along with David Rumelhart and Ronald Williams, Hinton published a paper entitled “Learning representations by back-propagating errors”. In this paper they showed that neural nets with many hidden layers could be effectively trained by a relatively simple procedure. This would allow neural nets to get around the weakness of the perceptron because the additional layers endowed the network with the ability to learn nonlinear functions. Around the same time it was shown that such networks had the ability to learn any function, a result known as the universal approximation theorem. And with that, neural nets were off to the races.

The algorithm works by taking the derivative of the network’s loss function and back-propagating the errors to update the parameters in the lower layers, hence the common moniker backprop. Though Rumelhart, Hinton and Williams are often credited for inventing backprop, this is disputed by some. There is something of a long standing controversy between the deep learning “conspiracy” of Geoff Hinton /Yann Lecun/Yoshua Bengio and Jürgen Schmidhuber as to who should actually be credited with several key developments, but that’s an issue best left tabled for now.

This algorithm lead to some early successes, notably in training convoluational neural nets (aka CNNs, also referred to using the less pronounceable convnets) to recognize handwritten digits, a project which was speared headed by Yann Lecun at AT&T Bell Labs. Below is a gif of Yann’s convnet reading a check:

Unfortunately, neural nets were in for another deep freeze. The approach didn’t scale to larger problems, and by the 90s the support vector machine (SVM) became the method of choice, and neural nets were moved back into storage. In hindsight, neural nets were simply an idea before their time, but it would be another 10-15 years before data and computing power were such that neural nets would finally be able to reach their final form.

Rebranding as ‘Deep Learning’ (2006)

Around 2006, Hinton once again declared that he knew how the brain works, and introduced the idea of unsupervised pretraining and deep belief nets. The idea was to train a simple 2-layer unsupervised model like a restricted boltzman machine, freeze all the parameters, stick on a new layer on top and train just the parameters for the new layer. You would keep adding and training layers in this greedy fashion until you had a deep network, and then use the result of this process to initialize the parameters of a traditional neural network. Using this strategy, people were able to train networks that were deeper than previous attempts, prompting a rebranding of ‘neural networks’ to ‘deep learning’. If you go to deeplearning.net, which I believe is owned by MILA, the title proudly declares

Deep Learning… moving beyond shallow machine learning since 2006!

in recognition of this transition.

The Breakthrough (2012)

With the renewed interest brought on by unsupervised pre-training, more and more neural network papers began to trickle out of several research labs. Then came a relative break through using deep nets for speech recognition where, for one of the first times, a neural model achieved state of the art. There had been a saying, usually attributed to JS Denker, that went:

Neural networks are the second best way to do almost anything

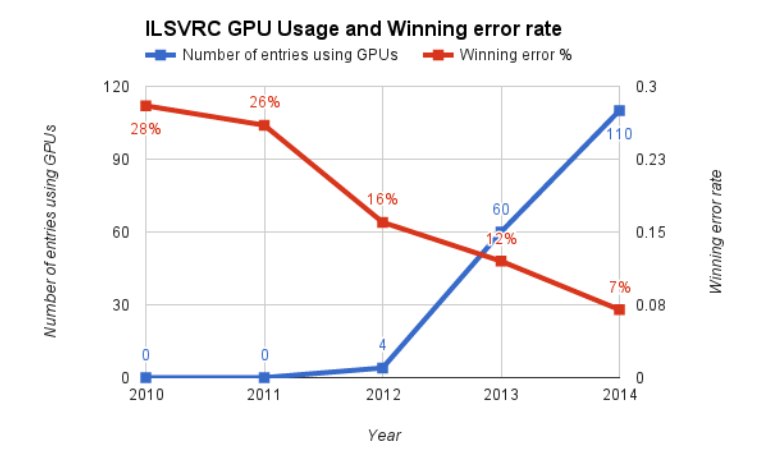

However, as neural nets started surpassing traditional methods, this became less and less true. Things would finally come to a head in 2012 on the Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge(LSVRC). In 2010, a large database known as Imagenet containing millions of labeled images was created and published by Fei-Fei Li’s group at Stanford. This database was coupled with the annual LSVRC, where contestants would build computer vision models, submit their predictions, and receive a score based on how accurate they were. In the first two years of the contest, the top models had error rates of 28% and 26%. In 2012, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoff Hinton entered a submission that would halve the existing error rate to 16%. The model combined several critical components that would go one to become mainstays in deep learning models.

Probably the most important piece was the use of graphics processing units (GPUs) to train the model. GPUs are essentially parallel floating-point calculators with 100s-1000s of cores. The speedup offered by GPUs meant they could train larger models, which led to lower error rates. They also introduced a method to reduce overfitting known as dropout and used the rectified linear activation unit (ReLU), both of which are now bread and butter components in modern deep learning. The network went on to become known as “Alexnet” and the paper describing it has been cited nearly 10,000 times since it was published at NIPS in 2012. Here is a graph showing the error rate on Imagenet over time, note the precipitous drop in 2012 and the huge uptick in teams using GPUs:

Many important innovations would come after this result, but I think it’s safe to say this is the moment when the deep learning levy finally broke. Many are becoming convinced that we are in the midst of a Great AI Awakening and billions are being spent by companies to stockpile AI talent and technology. It’s hard to know what will come next and the extent to which deep learning will play a role, but for now, it does feel like we’ve experience a paradigm shift in machine learning that is here to stay.

What’s changed? Why now?

Many of the core concepts for deep learning were in place by the 80s or 90s, so what happened in the past 5-7 years that changed things? Though there are many factors, the two most crucial components appear to be availability of massive labeled data sets and GPU computing. Here’s a run down of factors that seem to have had a role in the deep learning revolution:

- Appearance of large, high-quality labeled datasets - Data along with GPUs probably explains most of the improvements we’ve seen. Deep learning is a furnace that needs a lot of fuel to keep burning, and we finally have enough fuel.

- Massively parallel computing with GPUs - It turns out that neural nets are actually just a bunch of floating point calculations that you can do in parallel. It also turns out that GPUs are great at doing these types of calculations. The transition from CPU-based training to GPU-based has resulted in massive speed ups for these models, and as a result, allowed us to go bigger and deeper, and with more data.

- Backprop-friendly activation functions - The transition away from saturating activation functions like tanh and the logistic function to things like ReLU have alleviated the vanishing gradient problem

- Improved architectures - Resnets, inception modules, and Highway networks keep the gradients flowing smoothly, and let us increase the depth and flexibility of the network

- Software platforms - Frameworks like tensorflow, theano, chainer, and mxnet that provide automatic differentiation allow for seamless GPU computing and make protoyping faster and less error-prone. They let you focus on your model structure without having to worry about low-level details like gradients and GPU management.

- New regularization techniques - Techniques like dropout, batch normalization, and data-augmentation allow us to train larger and larger networks without (or with less) overfitting

- Robust optimizers - Modifications of the SGD procedure including momentum, RMSprop, and ADAM have helped eek out every last percentage of your loss function.

Most of these improvements have been driven by empirical performance on a standard set of benchmarks. There isn’t a ton of theoretical justification (though there is some) for many of these techniques, which leads to the following hypothesis:

Deep Learning Hypothesis: The success of deep learning is largely a success of engineering.

I don’t think this is a controversial position, and it’s not meant to minimize the success of deep learning, but I think it’s a fair characterization of how the state of the art has been pushed forward.

How can you stay current?

This field moves fast, and papers get old on a timescale of months, so keeping your finger on the pulse can be tough. I’ve developed a few coping mechanisms to try and help drink from the deep learning firehose:

- Read arXiv, and specifically the machine learning subsection. Close to 100% of deep learning papers get posted in some form on arXiv, so it will always be the definitive source for the cutting edge. The problem is that the volume of new work coming out is too large for any one person to consume. The main way to cope is a combination of social media like twitter and reddit and blogs from individuals and various research groups.

- arxiv-sanity is a machine learning (though not deep learning!) powered tool from Andrej Karpathy to help you shift through the vast swaths of research that is produced daily. Makes it easy to find papers relevant to your interests and even comes with a Netflix style recommendation engine.

- The keras blog has a lot of great tutorials on how to implement state of the art models in keras.

- The machine learning subreddit contains links to and discussions of the latest and greatest papers. Like all online communities, it can occasionally devolve into unproductive infighting, but I still find it to be tremendously useful.

- The OpenAI blog - Mainly focused on GANs and reinforcement learning

- Google research blog - All of Google research, but with a huge serving of deep learning since this is one of their main areas of focus.

- Subscribe to the talking machines podcast. Co-hosted by Ryan Adam and Katherine Gorman, talking machines is one of my favorite podcasts. Now two full seasons (with more to come!) of interviews with luminaries of the field and discussion of the latest and greatest papers. Highly recommended!

- Adrian Colyer’s blog ‘The Morning Paper’. Adrian write summaries of new CS papers pretty frequently, and many (if not most) are about recent events in deep learning. Definitely a great way to quickly get the Cliff’s notes for new papers.

- Twitter - this is probably the best way to stay up to date, because everything happens in real time. Here is an incomplete list of who to follow to help get you started:

- Yann Lecun - Head of Facebook’s AI research lab. Giant of the field and tweets often. If you’re looking for some laughs or just want to #feelthelearn, check out the parody account Bored Yann Lecunn run by Jack Clark: Follow @ylecun

- Andrej Karpathy - Research scientist at OpenAI, also has a great blog: Follow @karpathy

- Ian Goodfellow - Researcher at OpenAI, creator of generative adversarial networks(i.e. GANs), explainer of adversarial examples, world’s most trustworthy last name: Follow @goodfellow_ian

- Francois Chollet - Creator of keras, researcher at Google: Follow @fchollet

- Russ Salakhutdinov - Director of AI Research at Apple and professor at CMU: Follow @rsalakhu

- Fei-Fei Li - Imagenet creator, Stanford professor and director of the Stanford AI lab, Chief Scientist at Google Cloud: Follow @drfeifei

- Andrew Ng - Cofounder of coursera, former Standford professor, Chief scientist at Baidu: Follow @AndrewYNg

- Sander Dieleman - Creator of the lasagne deep learning framework and research scientist at Deep Mind. Also has a great blog with some epic Kaggle contest write ups. You can learn a lot just by reading how Sander approaches a Kaggle contest: Follow @sedielem

- Hugo Larochelle - Google Brain researcher: Follow @hugo_larochelle

- Rachel Thomas - Cofounder of fast.ai, a fantastic deep learning MOOC: Follow @math_rachel

- Andrew Beam - Your humble narrator. I’m not as prolific a tweeter as some on this list, but I try to share papers and projects I find interesting and/or important, with a special focus on healthcare and medicine: Follow @AndrewLBeam

Additional References:

- Deep Learning in a Nutshell: History and Training from NVIDIA

- A Concise History of Neural Networks - A well-written summary from Jaspreet Sandhu of the major milestones in the development of neural networks

- A ‘Brief’ History of Neural Nets and Deep Learning - An epic, multipart series from Andrey Kurenkov on the history of deep learning that I highly recommend.